Who can be called a hero? What kind of person should a hero be? Must it be a winner of a battle, a famous politician or a religious figure? I donít think so. In my opinion there are heroes in every family. The memory of them will always dwell with their descendants.

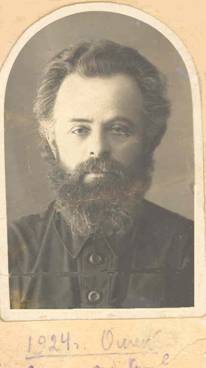

I want to say a word or two about my great-grandfather Alexander Dubnitskiy.

He was born in Kiev (Ukraine) in 1879. All of his folks were priests, so Alexander, following a family tradition, entered a religious school, called bursa, in 1889. After graduating, in 1897, he was offered to continue his education in Ecclesiastical Academy. But by that time he had understood that religion didnít come to be the focal point in his life, that was why he decided to become a volunteer in an infantry regiment.

At the age of 26 my great-grandfather had already decided what his future profession would be like. He chose an occupation that seemed to be interesting for him and in 1905 he entered Kharkov Veterinary Institute. Alexander finished the institute cum laude and began to work as a state physician. Later he was sent to Akmolinsk region (in Kazakhstan) to fight with the plague. Being 32 years old my great-grandfather began to work in Omsk Veterinary Gymnasium and at the same time he continued his scientific work. He became a PhD in 1914.

At the beginning of the World War I Alexander went to the regular army as a veterinarian. After October revolution he left the army. He refused to swear to the new government, motivating it like that: ďAn honest man takes the oath of allegiance only once.Ē In December 1917 my great-grandfather was appointed a department manager of cattle breeding in Omsk region.

Alexander was married twice and trained eight children. And besides their own children he and his second wife, Elsa Funke, adopted a girl who was made an orphan after her parentsí death during the famine in the Volga region. All children got higher education. In 1925 great-grandfather with his family returned to Kiev and worked as associate professor in Kiev Veterinary Institute till 1931, when in the first wave of repressions he was sent out to Siberia. Repressions are the measures of political control undertaken against political opponents. The repressed people were sent to far away corners of the Soviet Union, repressed people turned out to be guiltless and incurred repressions because of slander. For example, my great-grandfather was slandered for the reason that he had told a political joke where the name of Stalin had been mentioned in a humorous aspect. Unfortunately, the practice of denunciations was widely spread in the Soviet Union, generally because of the financial rewards which were given to informers.

The first years in Siberia he and his family lived very poorly, they were thwacked together in one room. Alexander continued to pursue science. There always were eight little children beside him, and they were very noisy. But great-grandfather never shouted or was angry at them Ė he was happy to be embosomed with joyful and expansive creatures. He adored his children.

Great-grandfather was a really compassionate person. Working as a veterinarian, he had no right to treat people. But in the remote Siberian village, where he had been sent to vet animals, there was no expert in human illnesses. That was why all the diseased went to Alexander and he provided them with medical care in spite of the oath he had taken. Luckily, all his patients were honest and grateful people: no one put the finger on him though his medication went beyond the law and deserved an exile.

My great-grandmother Elsa worked out to go with the children to her husband. Alexander labored in the Altai, in Tobolsk, in the north of Omsk region; he dealt with the noisome pestilence of anthrax. Along with his family he later moved to Tobolsk where he worked as a teacher in a Zoological veterinary technical school to the end of his life.

I think that my great-grandfather is a real hero, and all my relatives and me remember and respect him.

Kate Savinkina, Form 10M, Lyceum 130

Novosibirsk, Russia